New Study Calls for a Rethink of Cooperation in Biology

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology and Princeton University shows that natural growth differences—not just strategic interactions— can have a crucial impact on cooperation in nature.

To the Point:

- Natural growth differences shape cooperation: The study reveals that differences in organisms’ natural growth rates can play a decisive role in sustaining cooperative behavior—independent of strategic interactions.

- Challenge to classic models: Traditional game theory approaches like replicator dynamics fall short by ignoring ecological factors and natural variation.

- A fresh look at biological cooperation: Examples like enzyme-producing yeast are better understood when ecological realities are integrated into evolutionary theory.

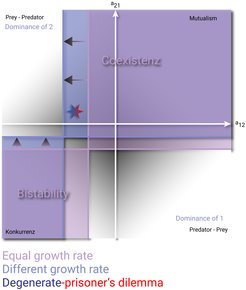

A new study from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology and Princeton University questions a long-standing assumption in evolutionary game theory. Traditionally, models assume that interactions alone determines success, but this research highlights the importance of natural growth differences. The findings suggest that cooperation in nature may not be as mysterious as previously thought and call for a new approach that integrates ecology into evolutionary models.

For decades, researchers have relied on a model called "replicator dynamics" to address how individuals with different strategies—such as cooperation or defection—compete for survival. However, this new study argues that these models overlook a critical factor: natural differences in growth rates between individuals, which can significantly influence evolutionary outcomes. Such differences can be integrated into the framework, but usually it requires the artificial inclusion of an additional strategic type.

“Our findings suggest that many past studies may have misinterpreted the role of cooperation,” says Dr. Arne Traulsen, co-author of the study. “If organisms have different natural growth rates, a behavior previously termed cooperation can persist even when classic game theory models predict its decline. At the same time the comparison between ecology and evolutionary game theory shows clearly a disconnect between game theoretical work on the evolution of cooperation and ecological work on mutualism. ”

The research provides a fresh perspective on cases like yeast that produce enzymes to break down sugars – and contain strains that do not produce enzymes. Previously, these were viewed as a battle between cooperators and freeloaders. However, the study suggests that the natural growth advantages of enzyme-producing yeast may be enough to sustain producers, without the need for complex strategic interactions.

By integrating ecological factors into evolutionary models, this research could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of how species interact, evolve, and maintain diversity. The study has implications for a wide range of fields, from microbiology to behavioral ecology.